Why is it that many individuals living with diabetes report feeling constantly hungry, even shortly after meals? Is this hunger psychological, or is there a medical explanation for it? Could it be due to the condition itself, the medication involved, or the body’s metabolic confusion?

These are valid questions, especially since persistent hunger known as polyphagia is one of the hallmark symptoms of both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

For those unfamiliar with the way diabetes affects appetite, it can seem contradictory. After all, one might assume that eating should reduce hunger. But in diabetes, the issue often lies not with how much someone eats but with how their body processes and utilises glucose.

The inability to efficiently convert food into usable energy can create a cycle of hunger that is difficult to manage and frustrating to endure.

Understanding this hunger requires a closer look at how diabetes influences insulin, blood sugar regulation, hormones, mental health, and lifestyle habits. This article explores the underlying mechanisms and provides clear explanations for the most common reasons why a diabetic might always feel hungry.

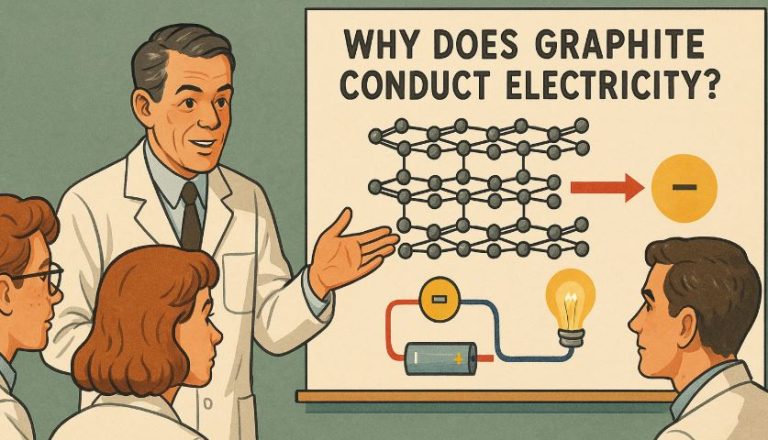

What Role Does Blood Sugar Play in Appetite Control?

Blood sugar or glucose plays a pivotal role in how the body regulates hunger and satiety. In non-diabetics, after eating a meal, glucose levels rise, and the pancreas releases insulin.

This hormone helps cells absorb glucose and convert it into energy. Once enough energy is available, hunger signals diminish.

However, in diabetics, this process is often disrupted. In type 1 diabetes, the body doesn’t produce insulin, whereas in type 2 diabetes, the body becomes resistant to it.

As a result, even though there may be plenty of glucose in the bloodstream, it doesn’t reach the cells efficiently. The cells remain starved, and the brain interprets this as hunger, prompting the person to eat again.

This false signal leads to a vicious cycle eat, but still feel hungry, eat again, and risk a blood sugar imbalance.

When blood sugar drops too low (hypoglycaemia) or spikes too high (hyperglycaemia), the brain’s hunger centres are activated again, further compounding the issue.

Can Diabetes Medications Make You Hungrier?

Certain medications prescribed for diabetes can indeed increase hunger as a side effect.

For example, insulin, which is commonly used by both type 1 and advanced type 2 diabetics, is known to cause increased appetite, especially if dosed improperly.

This is because insulin works to lower blood glucose levels. When these levels drop too quickly or go below normal, the body triggers hunger in an attempt to raise blood sugar again.

Other medications, such as sulfonylureas (e.g., glipizide or glimepiride), stimulate the pancreas to release more insulin. While effective in managing glucose, they can also increase the risk of hypoglycaemia and subsequent hunger.

If medication-related hunger is persistent, it is essential to review the dosage and type of treatment with a healthcare provider. Adjustments may be necessary to balance effective blood sugar control with minimal side effects.

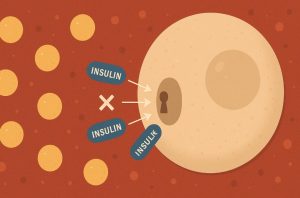

How Does Insulin Resistance Affect Hunger Levels?

Insulin resistance, a common feature of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes, is a condition in which the body’s cells become less responsive to insulin.

This means that glucose remains in the bloodstream instead of entering cells where it can be used as energy. Despite elevated blood sugar levels, the body’s cells effectively starve.

This internal starvation signals the brain to increase appetite, leading to feelings of constant hunger. People may feel compelled to eat more, particularly carbohydrates, in an effort to satisfy their body’s energy demands.

Unfortunately, without addressing insulin resistance, more eating leads to higher glucose levels and further insulin resistance a dangerous loop that can worsen diabetes management and overall health.

Is Hunger After Eating Normal for Diabetics?

It’s not uncommon for diabetics to report feeling hungry shortly after a meal. This may occur for several reasons.

First, meals that are high in simple carbohydrates such as white bread, sugary cereals, or processed snacks, cause rapid blood sugar spikes followed by quick drops.

These drops trigger hunger again, often within one to two hours of eating.

Second, if a meal lacks fibre, protein, or healthy fats, it won’t provide lasting satiety. Meals rich in these nutrients slow down digestion and help maintain a steady release of glucose, reducing hunger in the long term.

Finally, if insulin levels are unbalanced or not matched to meal composition (in the case of insulin users), this mismatch can also lead to post-meal hunger, especially if blood sugar drops too low.

10 Common Reasons Why a Diabetic Is Always Hungry?

1. Insulin Resistance and Glucose Imbalance

One of the most central factors driving constant hunger in individuals with type 2 diabetes is insulin resistance. In a healthy body, insulin acts as a key that unlocks cells to allow glucose the body’s primary energy source, to enter.

However, in someone with insulin resistance, the body’s cells become less responsive to this hormone. As a result, although glucose remains in the bloodstream, it cannot be efficiently absorbed and utilised for energy.

This creates a paradoxical situation: the bloodstream is rich in sugar, yet the cells are effectively starving. In response, the brain receives signals indicating an energy shortage, which it interprets as hunger.

The body then urges the person to eat more, especially carbohydrate-rich foods, which it mistakenly believes will provide the necessary fuel.

However, without resolving the underlying resistance, this additional intake merely raises blood sugar further and worsens the condition over time.

This ongoing cycle of poor glucose absorption, elevated blood sugar, and continuous hunger can be extremely frustrating and difficult to manage without targeted medical and nutritional intervention.

Addressing insulin resistance often requires a combination of medication, exercise, weight management, and dietary changes focused on lowering the glycaemic load of meals.

2. Blood Sugar Highs and Lows

Fluctuating blood sugar levels, whether too high (hyperglycaemia) or too low (hypoglycaemia), play a significant role in the regulation of appetite and can often lead to persistent hunger in diabetics.

When blood sugar is high, as commonly seen after consuming high-glycaemic foods or due to poorly managed diabetes, the glucose in the blood is not effectively absorbed into the body’s cells.

This again leads to a situation where, despite having energy available in the blood, the body behaves as if it is fasting. Hunger signals are then sent in an attempt to correct this perceived lack of energy.

Conversely, when blood sugar drops rapidly either from a delayed meal, excessive insulin, or overexertion, the brain senses an energy crisis.

The body responds immediately by triggering strong feelings of hunger.

This is especially evident in hypoglycaemic episodes, where symptoms such as dizziness, sweating, trembling, and confusion are accompanied by an intense, often uncontrollable desire to eat, typically high-sugar foods that can quickly restore blood glucose levels.

Over time, repeated cycles of high and low blood sugar disrupt the body’s natural hunger and satiety cues, making it difficult to distinguish between real physiological hunger and a glucose imbalance-induced craving.

This makes consistent blood sugar monitoring and dietary discipline essential in managing hunger effectively.

3. Uncontrolled Type 1 or Type 2 Diabetes

Whether someone has type 1 or type 2 diabetes, poor management of the condition can result in a persistent sense of hunger.

This often occurs when insulin levels whether natural or supplemented, are not aligned properly with blood glucose levels.

In type 1 diabetes, the pancreas produces little to no insulin, and individuals rely entirely on external insulin to regulate their blood sugar. If insulin is underdosed, glucose cannot enter the cells, leaving the person feeling tired, hungry, and irritable.

If overdosed, it can cause hypoglycaemia, which also leads to hunger. The challenge lies in achieving the delicate balance needed to match insulin doses with food intake, activity levels, and overall health status.

In type 2 diabetes, hunger may stem more from insulin resistance than a lack of insulin.

However, when blood sugar levels remain consistently high due to missed medications, poor diet, or lack of exercise, the body continues to signal that it is not receiving enough energy, even when it is. This leads to a repetitive eating cycle that further destabilises blood sugar control.

The solution to this issue lies in optimised diabetes management, which includes regular blood sugar monitoring, adherence to prescribed treatment regimens, nutritional planning, and routine check-ups with a diabetes care team.

Without this structure, constant hunger is likely to persist, regardless of how much food is consumed.

4. Frequent Hypoglycaemia Episodes

Hypoglycaemia, or low blood sugar, is one of the most urgent and impactful causes of hunger in diabetics, particularly those who use insulin or insulin-stimulating medications like sulfonylureas.

When blood glucose falls below normal levels, the body reacts by launching a full-scale alert to correct the problem as quickly as possible.

This reaction includes the release of hormones such as adrenaline and cortisol, which heighten awareness and anxiety, as well as glucagon, which signals the liver to release stored glucose.

Simultaneously, the brain sends powerful hunger signals urging the person to eat immediately, preferably something sugary to restore balance. This hunger can be intense and overwhelming, often leading to rapid, unplanned consumption of food.

If hypoglycaemia episodes occur frequently, the brain becomes conditioned to associate slight drops in blood sugar with the need to eat.

This can lead to a form of psychological hunger, where the individual feels compelled to eat not because they are calorically deprived, but because they are afraid of another hypoglycaemic episode.

Managing hypoglycaemia requires a fine-tuned approach: accurate insulin dosing, regular eating schedules, controlled carbohydrate intake, and emergency snacks in case of sudden lows.

Diabetics who frequently experience low blood sugar should work with their healthcare provider to adjust their treatment plan and prevent this cycle of fear-induced eating.

5. Glucagon and Hormonal Dysregulation

The hormonal regulation of appetite and blood sugar involves a delicate interplay between several key players, primarily insulin and glucagon.

In a healthy person, these hormones work in opposition to maintain glucose balance: insulin lowers blood sugar after meals, while glucagon raises it during fasting or low-sugar states by prompting the liver to release stored glucose.

In diabetics, especially those with long-term or poorly controlled conditions, this hormonal balance can become impaired.

Glucagon may be secreted inappropriately for instance, during a meal when blood sugar is already high, leading to additional glucose being released into the bloodstream.

This not only disrupts glucose homeostasis but also contributes to the sensation of hunger, as the liver’s energy signals conflict with the actual food intake.

Additionally, other hormones such as ghrelin (which stimulates appetite) and leptin (which signals fullness) may also be disrupted in diabetics. This hormonal dysregulation confuses the body’s hunger and satiety signals, making it difficult for diabetics to determine when they are truly hungry and when they are not.

Such dysfunctions are often compounded by factors like poor sleep, stress, medication use, and long-term blood sugar variability.

Addressing them usually requires comprehensive diabetes care, including regular endocrine assessments, improved glycaemic control, and dietary strategies that support hormonal balance.

6. Emotional and Stress-Driven Eating

One of the less recognised but highly influential causes of excessive hunger in diabetes is emotional eating, often triggered by chronic stress, anxiety, or depression.

Living with a long-term condition like diabetes can itself be emotionally taxing. Constant monitoring, dietary restrictions, and the fear of complications can weigh heavily on an individual’s mental health. When these emotional burdens go unaddressed, the body may turn to food for comfort.

Stress activates the release of cortisol, a hormone that not only increases blood sugar but also stimulates appetite, particularly cravings for high-fat, high-sugar foods.

This can create a cycle in which emotional distress leads to overeating, which then causes guilt or worsens diabetes control, thereby generating even more stress.

Moreover, individuals with diabetes may eat not out of physical hunger but in response to fatigue, boredom, loneliness, or frustration.

These emotional cues are easy to confuse with genuine hunger, especially if someone is already dealing with erratic blood sugar levels.

Addressing emotional eating requires a holistic approach. Psychological support, mindfulness techniques, stress-reducing activities such as exercise or meditation, and working with a therapist or counsellor experienced in chronic illness can all help reduce the urge to eat in response to emotional triggers rather than true physiological need.

7. Medication Side Effects

Many diabetics experience increased hunger due to the side effects of medications used to control their blood glucose levels.

While these medications are essential for maintaining metabolic balance, they can inadvertently lead to polyphagia, particularly if doses are too high or not well-matched to the patient’s nutritional intake.

Insulin, whether administered via injection or pump, is the most common medication associated with increased hunger. Its primary function is to reduce blood glucose by facilitating its entry into cells.

However, if insulin lowers blood sugar too quickly or too much, the body interprets this as a shortage of energy and triggers hunger in response. Patients may find themselves eating more frequently or craving carbohydrate-rich foods shortly after insulin doses.

Other medications, particularly sulfonylureas (such as glipizide or gliclazide), stimulate the pancreas to release more insulin. These drugs can cause unpredictable dips in blood glucose, resulting in feelings of shakiness and sudden hunger.

In some cases, diabetics may also be prescribed medications for coexisting conditions such as steroids, antidepressants, or beta-blockers, which can influence appetite regulation either directly or indirectly.

It is crucial that individuals experiencing unexplained or excessive hunger consult their GP or diabetes specialist to review their medication regimen.

Adjusting doses, switching drug classes, or aligning meals more precisely with treatment schedules may help minimise this side effect.

8. Nutrient Deficiency (Fibre, Protein, Fat)

Not all calories are equal when it comes to controlling hunger. A diet lacking in key nutrients particularly fibre, protein, and healthy fats, can lead to quicker digestion, faster blood sugar spikes, and shorter periods of satiety.

This is especially problematic for diabetics, who rely on balanced nutrition not just for managing weight, but for stabilising glucose levels.

Fibre, found in whole grains, legumes, vegetables, and fruits, slows the digestive process and helps regulate blood sugar. Protein supports muscle maintenance and also contributes to longer-lasting fullness.

Healthy fats, such as those from avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil, take longer to digest and further extend satiety.

When meals are built around refined carbohydrates, sugary snacks, or processed convenience foods, blood sugar levels rise quickly and then crash, prompting hunger not long after eating.

Even if caloric intake is technically adequate, the body can still feel unsatisfied due to these rapid metabolic swings.

To reduce persistent hunger, diabetics should aim to build each meal with a balance of macronutrients: moderate amounts of complex carbohydrates, sufficient lean protein, and a source of healthy fat, all supported by high-fibre vegetables or grains.

Consulting with a registered dietitian can be particularly helpful in crafting a meal plan that meets these goals without compromising blood sugar control.

9. Poor Eating Habits and Skipped Meals

Many people with diabetes unintentionally worsen their hunger cycles by engaging in inconsistent eating patterns, such as skipping meals, eating at irregular intervals, or consuming unbalanced portions.

These habits can disrupt the body’s natural rhythm of glucose utilisation and hormone secretion, leading to more frequent feelings of hunger and less control over appetite.

Skipping meals, particularly breakfast, may initially seem like a way to reduce calorie intake. However, doing so can lead to low blood sugar levels later in the day, especially if the next meal is delayed or imbalanced.

This often triggers a compensatory response: overeating at the next opportunity or snacking impulsively, particularly on high-sugar or high-carb foods.

Inconsistent eating also affects insulin effectiveness. Those on scheduled insulin therapy may find that missing a meal causes blood sugar to dip dangerously low, requiring immediate food intake to stabilise it.

This reactive style of eating contributes to confusion around true hunger signals and can make it difficult to establish a sustainable routine.

Establishing a regular meal pattern, ideally with three balanced meals and one or two planned snacks per day, helps maintain stable glucose levels and supports a more predictable appetite.

The timing of meals should ideally be consistent from day to day, and carbohydrate intake should be evenly distributed.

10. Underlying Medical Conditions

While diabetes itself is a significant driver of excessive hunger, it’s important not to overlook the possibility of underlying medical conditions that can also affect appetite and complicate diabetes management.

One such condition is hyperthyroidism, in which an overactive thyroid accelerates the body’s metabolism. This can lead to increased energy demands, higher caloric burn, and persistent hunger, sometimes mistaken for poor diabetes control. If left untreated, it can also worsen blood sugar instability.

Another condition often seen in women with type 2 diabetes is polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), which involves insulin resistance and hormonal imbalances.

PCOS can contribute to both weight gain and increased hunger, making diabetes management more challenging.

Digestive disorders such as gastroparesis (a diabetes-related complication where the stomach empties slowly) can also interfere with hunger signals.

Some individuals may feel hungry soon after eating because their body hasn’t absorbed nutrients properly, while others may avoid food due to nausea or bloating, leading to erratic blood sugar and hunger patterns later on.

Chronic stress, depression, and certain neurological disorders may also disrupt hunger regulation pathways in the brain.

In cases where hunger persists despite good glycaemic control, it is advisable to consult with a healthcare provider for a thorough medical evaluation.

Blood tests, hormone panels, and dietary reviews can help identify whether an unrelated condition is contributing to appetite disturbances.

Summary of the 10 Reasons Why a Diabetic Is Always Hungry?

| No | Cause | How It Affects Hunger | Recommended Approach |

| 1 | Insulin Resistance | Prevents glucose from entering cells, causing constant energy starvation and hunger | Improve insulin sensitivity through diet, exercise, and medication adjustments |

| 2 | Blood Sugar Fluctuations | Highs and lows confuse the body’s hunger signals, triggering cravings | Monitor glucose levels, avoid high-GI foods, eat balanced meals |

| 3 | Poorly Managed Diabetes | Inconsistent blood sugar control increases hunger and impairs satiety signals | Follow a structured treatment plan, review medication, monitor regularly |

| 4 | Frequent Hypoglycaemia | Low blood sugar prompts urgent hunger and sugar cravings | Adjust insulin dosing, carry healthy snacks, avoid long gaps between meals |

| 5 | Hormonal Dysregulation (e.g., Glucagon) | Disrupted hormonal signals interfere with appetite control | Address through medical management, balance meals, monitor hormonal markers |

| 6 | Emotional/Stress-Driven Eating | Cortisol and emotional triggers stimulate appetite even without physical need | Practise stress management, consider therapy or counselling |

| 7 | Medication Side Effects | Drugs like insulin or sulfonylureas can increase appetite | Consult GP to review and adjust medication |

| 8 | Nutrient Deficiency | Low fibre, protein, or healthy fat leads to poor satiety and faster return of hunger | Increase intake of protein, fibre, and healthy fats in every meal |

| 9 | Poor Eating Habits | Skipped meals or irregular timing causes blood sugar crashes and rebound hunger | Establish consistent meal patterns and portion control |

| 10 | Underlying Medical Conditions | Conditions like hyperthyroidism or PCOS may increase appetite | Seek medical evaluation to diagnose and treat underlying health issues |

Conclusion: Addressing Hunger in Diabetes with Awareness and Action

Persistent hunger in diabetes is not merely a matter of willpower or poor diet it’s a symptom rooted in physiological imbalances, medication effects, lifestyle patterns, and sometimes underlying health conditions.

Understanding the reasons behind this hunger is the first step towards better management.

By stabilising blood sugar, improving dietary quality, managing stress, and consulting healthcare professionals when needed, people with diabetes can take back control of their appetite. With the right strategies, constant hunger doesn’t have to dominate daily life.

FAQs: Hunger and Diabetes Explained

What causes constant hunger in diabetes?

Usually, insulin resistance, blood sugar imbalances, or poorly managed medication.

Can diabetes medication make you hungrier?

Yes, especially insulin and sulfonylureas, which can lower blood sugar quickly.

Is it normal for diabetics to feel hungry after eating?

Yes, if meals are low in fibre or cause rapid blood sugar drops.

How can I stop feeling hungry all the time with diabetes?

Eat balanced meals, monitor glucose, and address emotional eating.

Does stress make diabetics eat more?

Yes, stress raises cortisol, which increases appetite and cravings.

What foods help reduce hunger in diabetes?

High-fibre vegetables, lean proteins, healthy fats, and low-GI carbs.

When should I see a doctor about my hunger?

If it persists despite proper meals and glucose control, seek medical advice.

READ NEXT: